Full Excerpt: Lou Reed's Nephew

By Jim Hanas (from Issue #3)

To read the full novel serialized on Substack, click here:

|

Lou Reed’s Nephew on Pedagogy I heard his voice as soon as I stepped off the elevator, muffled only a little by the security door. I swiped my card, releasing the lock with a satisfying click, and swung open the enormous glass slab. That’s when I heard him, Lou Reed’s Nephew, in full voice. “If one is to be respected by one’s peers,” he declared with a conviction that would become all too familiar, “one must speak in the ways others do, even if this is not speech at all, but text. …Here, here. Hold it like this. Get it in your two thumbs. Trust it. Trust the tiny computer inside. It knows how to talk. …Look. When you try to type ‘cool’ it tries to change it to ‘book.’ Isn’t that funny? When was the last time you read a book?” “…” “That’s right. Trust your thumbs… and the tiny computer.” I went to my rented cubicle, a uniform enclosure lined with brown-beige fabric, the fifth one down in the second row from the elevator. Its walls were higher than in a regular office to deter, if not prevent, late-night coders from foraging inside for snacks and thumb drives. It occurred to me daily—as Ulugbek and I chased our ever-receding go-live date—that working inside was like working at the bottom of a cheaply upholstered grave. I undid the opening, secured by two panes of corrugated plastic joined by a clumsy hinge. This was before such spaces became corporatized and manicured, like hotel lobbies or French inns. The impatient South African who owned the place had done his best, roughly brushing every aluminum surface—from the refrigerator to the elevator doors—with a Black & Decker grinder, but the place retained the feel of a sweatshop and a lingering smell of grease. I sat down and tried to get a glimpse of my new neighbor as I plugged in my laptop. I took it home every night after my previous one vanished, along with a clear plastic cylinder of Twizzlers a customer success manager sent me with her business card tucked inside and a Blackberry I had clung to for too long. Swiveling in my chair, I saw that his panes were pulled closed. I could only make out a slim figure—like a killer outside a shower—wildly waving its arms. “That’s all we have time for now,” he announced. The panes opened. I got my first look. He was 26. Or younger. Not older. He had dark hair. Narrow nose. Narrow face. Unremarkable but expensive glasses. Preppy clothing laundered by three decades of hip-hop. He wore a pressed, striped oxford, untucked from crisp, stiff jeans that broke as perfectly across the shell-capped toes of his sneakers as his shirttail fell just past his beltloops. As he pulled back the panes, I saw his clients, both female, wedged into a space no larger than a fitting room. The first was in her late thirties. My age, more or less. I was 43 but still rounding down. She had the glow of a determined divorcee. She might still have been married, but such was the availability of her glow. She reminded me of Renata’s college acquaintances, who we seemed to run into in every bookstore aisle and juice bar in our neighborhood. It was mid-January, when such New Yorkers dress like extras from The Matrix or Chitty-Chitty Bang, though this woman had attempted a difficult hybrid. She wore black Lycra tights—as snug as jodhpurs but decidedly thinner and infinitely more futuristic. These disappeared into a pair of shrimp boat-grade galoshes stamped with a repeating pattern of tiny skulls. Above the waist, she was a woolly Victorian. She wore an over-sized black and red checked coat, topped with a coy newsboy made from the same fabric. She was not, however, wearing antique automotive goggles around her yoga-toned neck. These she had surrendered to her daughter—a perfect little Emma, the most popular name for 10-year-old girls in Manhattan and parts of Brooklyn in 2013, the year of my encounter with Lou Reed’s Nephew. Emma also wore tights and a newsboy, a black and red coat like her mother’s, gel-injected death booties, the useless pair of goggles slung around her pale neck. She held a freshly unboxed iPod Touch between her peach-colored thumbs, pressing away, oblivious to the fuss taking place around her entirely for her benefit. Mom took out her checkbook, an object that confused Lou Reed’s Nephew. When she was done scribbling, he took the check between his fingers like a tissue he’d found on the train. “Keep it up,” he told the girl, who ignored him, responding only to her mother’s hand on the back of her neck, guiding her out of the cubicle, down the aisle, and to the elevator. He walked behind them, calling to them as they slowly fled. “Trust your thumbs!” he said. He returned, shaking his head. He walked into his opening and turned to catch me staring. “You teach texting?” I asked, flummoxed. “As much as I can,” he said. “Hard to find students?” “Hard because I don’t know anything about it.” “About texting?” “As little about that as about anything else.” “You sound convincing,” I said. He sat in his chair and swiveled toward me. He held his phone in his lap—trusting his thumbs—looking up only occasionally. “If you don’t know anything, confidence goes a long way,” he said. “Scolding, too. Mothers love scolding. Especially if you have a British accent. Or a French one. I forgot my accent when I picked up the phone on this one so I’m stuck charging American rates. It’s harder.” “Why?” “Because everyone knows Americans are stupid,” he said. “Especially Americans.” “You are an American.” “Of course.” “And you don’t know anything about texting?” “What is there to know? It’s like talking. And that’s not what they pay me for anyway. They pay for a performance. A woman comes in and I talk to her for a few minutes—possibly with a Belgian accent—and I tell her that she is doing the right thing. ‘You are doing the right thing, Andrea,’ I say, being sure to use her name.” “You’re a student of the human condition.” “Yes. It’s crucial to use people’s names when you talk to them. It helps them narrate your interaction when they’re at dinner with friends, who are all potential customers. Boring people have their own literary point of view, I’ve noticed. It’s innovative, formally, but completely exhausting. I call it free second person indirect. It’s a technique, like free indirect or third person close, but they don’t teach it in writing programs because it’s so awful. “People usually speak in the first person, of course, but truly boring people invariably drift into quotations of other people addressing them in the second person, and these people are always complimenting them. “‘That’s so clever, Andrea, hiring a Norwegian to teach your daughter to text.’” “Do they always use their own names when telling these stories?” “Frequently. It’s one of the conventions of the form. So, I help Andrea along by including her name, the way “Ambulance” appears backwards on the front of ambulances so you can read it in your rearview mirror, or the way brands put ‘my’ before logos so you will think they belong to you rather than the other way around. Then I tell Andrea that her child’s socialization is crucial to popularity. And popularity, once a dirty word to Andrea, is making a comeback because it is a guard against bullying. For Andrea, bullying is like GMOs and tone deafness rolled into one.” “That woman’s name was Andrea?” “I don’t remember. But Andrea—and her wine o'clock cohort—are obsessed with bullying. Though she probably pierced her tragus with a compass when she was 13 so she could stand out and attract a few bullies—those constant consorts of genius—Emma will be allowed no such risks. Emma will have her tragus pierced professionally. I don’t know about yours, but my parents understood that bullying and being bullied were rites of passage. Like sin and suffering.” “Your parents must be very old.” “Ancient.” he said. “And cross-addicted.” “You should write a memoir.” “Never,” he said. “I live by the old ways. If you’re crazy, keep it to yourself. It’s good for you and a favor to the rest of us.” “Well, if your story can help just one person…” “Memoirists are too easy on themselves,” he said. “Always setting the bar so low.” “You have a better idea?” “20% of adults 18-44. Help that many people or keep it in your drafts folder. We’ve got to draw a line with these people or they’ll eat us alive with their misery.” “I see.” “In any case, I tell Andrea she’s doing the right thing. I don’t say, ‘Because the world is scary and children are cruel.’ That goes without saying. We wouldn’t be talking—I in a whimsical Portuguese accent—if Andrea didn’t already believe that.” “That woman who just left? Was her name Andrea?” “Let’s see. No, here it says Stephanie.” He handled the check suspiciously. “Anyway, I don’t need to give Andrea or Stephanie fear, because she already has it.” “Was the child’s name Andrea?” “Of course not. That’s an old-fashioned name. The child’s name was Jane.” “A really old-fashioned name.” “So old it’s new. But names don’t matter. What I’m trying to explain to you is that the mother, whatever her name is, is afraid. She is afraid for her child who, in this case, is called Jane, and I am the solution to her Jane-based fear. I sit with the child—this Jane—knee-to-knee, thumbs-to-thumbs, and I teach her ‘how’ to text so she will fit in, find friends, and escape bullying.” Lou Reed’s Nephew threw air quotes around “how” as he spoke. “Why do you throw air quotes around ‘how’?” I asked. “Because I’m sure Jane knows more about it than I do. I have nothing to teach. I am only there for the fear. Jane and I both know this. I have no expertise, but I have a few talents. One is knowing how to talk to parents. Another is letting children know that I know their parents are idiots. I teach Jane nothing and Jane knows I have taught her nothing. Jane does understand, however, that this play about teaching her something is good for everyone—most of all for me and for her. “How much do you think such a service is worth?” “You’ve already said it’s worthless.” “That’s not what I said exactly. How much do you think she paid me?” He seized the check between two fingers and teased me with it. “Five thousand dollars.” “Afraid to guess? Afraid you might get angry?” “I guess five thousand dollars.” “Wrong. Five hundred.” “For an hour?” I was getting angry. “Fifty minutes.” “That seems like a lot.” “Andrea doesn’t mind.” I squirmed in my Aeron chair and worried that my new neighbor could sense my discomfort. Instead, he sunk into concentration on his flying thumbs, which he trusted completely. “Who is Andrea?” I asked one last time. Lou Reed’s Nephew on Typing “I took a copy of Walden to a job interview today,” Lou Reed’s Nephew bragged as he arrived at his cubicle late one afternoon. “Not much of a team player, Thoreau,” I said. “You hid it, I’m sure.” “Not at all. It sparked a great conversation.” “I’m guessing you didn’t get the job?” “I am certain of it,” he said. Other than not really teaching children how to text, I didn’t have a good idea of what Lou Reed’s Nephew did. Or intended to do. I had seen no more Andreas and several weeks had passed. In the meantime, he had decided I was a good audience for his daily observations, and I was glad to be distracted from the surges of anxiety produced by our ever-receding go-live date. “You are looking for a job?” “Not really,” he said. “But you never know. You know what they didn’t ask about, though? “Typing,” he blurted before I could answer. “They never ask about typing.” “Can you type?” “Who can’t type?” he said “But it used to be a whole career path. A thing people got paid to do.” “I suppose so, yes.” I took typing in high school, from a Miss Spenser who needled me for staring at my fingers instead of the lessons on etiquette we copied on the giant IBM Selectrics that held down the desks in her classroom like giant paperweights. She had enormous teeth and visible gums, an endless supply of sweater sets with tissues squirrelled up the sleeves, and a hairdo that must have required weekly visits to what were still called beauty parlors. The fifties, though faded, remained visible then. We watched its first-hand and second-hand TV, from The Lone Ranger and The Mickey Mouse Club to M*A*S*H and Laverne & Shirley. I played with a mess kit my grandfather—who had killed Nazis at the Battle of the Bulge—brought home from Korea. It barely felt antique as I folded and unfolded it, cooking invisible rations over imaginary flames. On a timeline from the Korean War to my year with Lou Reed’s Nephew, Miss Spenser’s typing class appeared at the exact midpoint, beneath a long shadow of waning expectations. “Now they don’t even ask about it,” Lou Reed’s Nephew said. “They assume you can type and are probably always right. I bet they never hire someone for a job that requires typing, then find out they can’t type.” “Because everyone can type.” “Because everyone can type,” he agreed. “What a shame.” “A shame?” “For the typists. Where did they go? Where are the memorials to this clerical genocide?” “I’m sure they just learned to use computers.” I thought about Miss Spenser. She probably hadn’t learned to use a computer. “Maybe,” Lou Reed’s Nephew snorted. “If they were lucky. If they were unlucky, their bosses learned to use computers and got rid of them.” “That doesn’t sound like bosses,” I said. “Taking on more work.” “If you say so,” he said. “I’ve never had a boss.” He sulked for a moment before suddenly perking up. “But maybe that’s not what happened,” he said. “Maybe the bosses didn’t learn to type. Maybe the typists became the bosses!” “That would be nice.” “It would be. But it’s still sad.” Lou Reed’s Nephew’s emotional roller coaster had hit another curve. He could move from elation to discouragement with ease, though it wasn’t clear whether these were part of the performance or genuine effects the performance had on him. Whatever his method, he was animated, like an actor. “How so?” I asked. “The typists became the bosses, but now they have to do their own typing.” “Where did all the typing money go?” “That’s what I’d like to know,” he sniffed. Lou Reed’s Nephew on Storytelling “Have you heard about storytelling?” Lou Reed’s Nephew asked. “What about it?” I asked. “That it’s what makes us human? That it gives our lives meaning?” “That sounds familiar,” I said. “Did you read it in a book?” “In a job description,” he said. “For a platform that helps people tell and share their stories.” “Another one?” “Of course,” he said. “Everything is a story now. Brands have stories. Rooms have color stories. Even stories have story worlds, which are stories about stories. We’re going to need lots of places to tell and share them. All these stories.” “It’s true. I do all my reading on shopping sites now,” I confessed. “They are all desperate to tell me stories.” I couldn’t sleep at night—pulled forward as I was by our ever-receding go-live date—so I roamed the internet looking for pithy histories, detailing how insignificant artifacts like nails or ice cubes had altered the course of history. I read about how the invention of the tumbler had made the Pyramids possible at The Bad Glazier. How artisanal bookcases led to the French Revolution at Crooked Timber. The secret history of the duvet and its role in the Reformation at Fourfold. I never bought anything—I wouldn’t trust these flimsy operations with my credit card—but I appreciated that they’d stepped into the non-fiction market. They even made me feel better about my sleeping habits. Everyone divided their nightly rest into two parts in the nineteenth century, according to the website of Procrustean Beds, a company that delivered California queen mattresses to your front door in package no thicker than a toilet paper roll. Without electricity, the night was long. People split it into stages, like a long journey. They woke up, visited neighbors, gossiped, ate, maybe had sex then slept until dawn. These stories soothed me with their upside-downness, reassuring me that my nocturnal insignificance might still somehow be important. “Maybe that’s where all the typing money went,” I said. “It’s actually kind of difficult to find things that are not stories,” Lou Reed’s Nephew said, ignoring my aside. “Well, they are what make us human.” “And give our lives meaning,” he said. Lou Reed’s Nephew gazed into the brown-beige fabric of his cubicle. “But if stories are what make us human and give our lives meaning, why do we have to work so hard at them? Isn’t this, what’s happening here—right now, with you and me—the story that makes us human, that gives our lives meaning? Why do we need help with that? Look at how effortless it is. Why corral these stories onto platforms for telling and sharing? Aren’t these platforms really enclosing and killing, rather than telling and sharing, the stories that make us human and give our lives meaning?” “What does it say there?” I asked. “It says here creating,” he said, squinting above his glasses at his laptop. “Via ‘activation of the Anthropocene talespace.’” Lou Reed’s Nephew on Literacy “You know what’s a scam?” Lou Reed’s Nephew looked up from a magazine, which he handled gingerly. His cubicle was spotless, except for a whiteboard he occasionally scrawled things on, and he never carried anything except his phone. He walked free, unencumbered, and I sensed that he regarded all physical objects—from checks to magazines—as threats to his breezy existence. “QR codes?” I guessed. “Augmented reality?” I guessed again before he had a chance to respond. “Haptic feedback?” “No,” he said. “Literacy.” “You are against reading?” “Reading is fine,” he replied. “It’s literacy I’m talking about.” “You’ll have to explain.” “Everywhere you look, there are charities and government agencies spending millions to expand literacy.” “Your point being?” “My point being that you don’t see do-gooders teaching people how to watch others unbox athleisure outfits or have strangers crinkle foreign currencies in their ears, yet all those activities are doing fine. Massive growth, year over year.” “Or scan QR codes.” “Or scan QR codes. Exactly! If the government made it its mission to stamp out ignorance of QR codes, we would be rightly outraged. Let the QR code cartels foot that bill! Yet spending taxpayer money to expand the user base of these letter puzzles”—he slapped the magazine with the back of his hand—“is treated like some unassailable virtue.” He was so mad he was spluttering. “You’re just angry because texting lessons aren’t covered by insurance, aren’t you?” I asked. “No comment,” he said. Lou Reed’s Nephew on Aging “There is an age past which the world doesn’t care about you anymore,” Lou Reed’s Nephew confided. I found his confession touching. “And what age is that?” “I don’t know. But I know I’m past it.” “You seem young for a midlife crisis.” I considered myself young for a midlife crisis, and I was almost twenty years older. “I sometimes catch myself thinking I have circled back and outsmarted it,” he continued. “But I know there comes a time when you can no longer be the next interesting thing.” “…” “Lists of interesting things never include old people, like you,” he continued, not sparing my feelings. “Lists are created by young people, who never believe in them more than when they are impatiently waiting to inhabit them. I see them on the subway, these youngsters, wearing pinned pants and porkpie hats—waiting for photographers to arrive. The women wear perfect little trench coats and those boots like stormtroopers’.” “How old are you, exactly?” He seemed indistinguishable from the people he described. “I arrived too old, maybe,” he said, wistfully. “I am concerned about you.” “Yesterday I went to look at an apartment,” he said. “It was being rented by a curvy young woman with calves like bowling pins. Inverted, I mean. They were lusty. She worked for a fashion website, or something, and was dressed like a secretary from December 1963—that crucial month between the Kennedy assassination and the Beatles’ arrival, when our popular culture hung in the balance. Pencil skirt. Sweater. Flats with little Tory Burch swastikas on them. I asked why it hadn’t been rented already and she said the people who’d looked at it so far had been younger. ‘My age,’ she said. ‘You know.’” “I am so sorry,” I consoled him. “But I did know,” Lou Reed’s Nephew continued. “More clearly than she could have understood. She was dwelling in the belief that she still might become somebody. That beacon lay before her, a lighthouse up ahead. And I know (but could not tell her, obviously, while she considered my application) that she will never be able to pinpoint the exact moment when she passed the lighthouse. She will only one day realize that she has.” “You’re killing me.” “Which is not to say that new beacons don’t occasionally materialize. They do, and they tantalize. But never do they convince as completely as that first great beacon.” “Did you at least get the apartment?” “No,” he said. “She gave it to a really old couple. People your age.” Beybi: Authority for Life On the first Tuesday of each month, Lou Reed’s Nephew took over one of the two small conference rooms on our floor from 10 to 2. Our rented cubicles entitled us to two monthly clock hours of Big Conference Room Time or four monthly clock hours of Small Conference Room Time. This was how Lou Reed’s Nephew spent his entire allotment. The foam core sign he set up on an easel outside the room said, simply, “Pitch Your Idea.” He explained all this to me one Tuesday after I had noticed his absence, only to find him alone in the Small Conference Room on my way to the bathroom. He sat so still the automatic lights had turned off, flickering on as I entered. “And people do it? They come in here and pitch you ideas?” “Usually a few.” “They are looking for investors?” “I’m sure.” “And you are looking to invest?” “Of course not,” he said. “Do they know that?” “Know what?” “That you’re not looking to invest.” “I have no idea. The sign says, ‘Pitch Your Idea,’ so they do. Sometimes a line forms.” “And?” “Terrifically entertaining.” “Can I join you?” “I suppose,” he said. “I am wary of groups larger than two. Factions form and I always end up in the minority.” Before he could elaborate, a baby-faced young man stuck his head in and asked, with impossible enthusiasm, “Is this where I pitch my idea?” “Yes,” Lou Reed’s Nephew said. “Come in.” I sat down in the chair next to Lou Reed’s Nephew so that we were at 10 and 2 o-clock of the small circular table. We invited our visitor to sit down at 6 o’clock, reflecting the dynamics of the situation. It took our visitor whole minutes to settle into the chair as he removed his hoodie and fumbled through his backpack for his laptop and hastily wrapped the cord of his headphones around them and stuffed them into his backpack like a child cramming clutter into a toy box. Everything about him seemed childish. His round cheeks still contained baby fat, which bulged at his wrists, knuckles, and—if you looked carefully—at his middle. This was somewhat concealed by the fact that he was basically wearing pajamas, soft jersey pants that puckered at the ankles and a too small t-shirt that strained around his shmooishness. His hair was thin in both senses: There wasn’t much of it and what there was lacked vitality. He looked, in every aspect, like a gigantic baby, foreshadowing what was to come. He took a deep breath, closed his eyes, and began. “Do you know why baby names have gotten so strange?” he asked. “Yes,” Lou Reed’s Nephew replied. “I mean, how many ways can you spell Madison, right?” “Right,” Lou Reed’s Nephew said. “And who would want to spell it even one way?” “Agreed.” Lou Reed’s Nephew’s responses had no effect. Our guest was working from a script with only one part. “I do know why,” Lou Reed’s Nephew said. I could see he relished derailing the pitch. “Would you like to know why?” “… OK.” “It’s simple math. No one wants to give their child the same name as someone they’ve slept with before their current partner. It leads to odd memories, feelings, and uncomfortable discussions. And now that people in the industrialized world postpone settling down and have more sexual partners per capita before choosing a mate, the available names for each child born…” “Slut shaming!” “Excuse me. What is that?” “I’m not sure,” the visitor blushed, realizing that calling out this infraction was not to his advantage. “But I believe you are doing it.” “So,” Lou Reed’s Nephew continued. “The universe of available names for each child born has been reduced by the union of their parents’ sexual histories, so new names have had to be manufactured.” “That’s an interesting theory,” the visitor said, politely, suggesting he’d heard it before. I waited for him to share his own hypothesis. “But the real reason,” he continued, “is an innate human instinct for SEO.” “Humans have an innate instinct for search engine optimization?” I blurted. Lou Reed’s Nephew shot me a glance, reminding me I was there at his invitation. “Why not?” he said. (If there would be factions, he would be in the majority.) “If Chomsky can have his ‘Language Acquisition Device,’ no theory can be too overdetermined.” “That’s why you get all these new spellings of Madison, for example,” our guest said, excited to have a defender. “Parents sense, from ambient sampling, that Madison, Maddison with a second ‘d,’ and even Madisyn with a “y” are becoming too competitive, so they move to the next available iteration.” “Because the more competitive names will be a handicap later in life,” I said, despite myself. “Where does the ‘y’ go?” Lou Reed’s Nephew asked. “Yes,” our visitor said, ignoring Lou Reed’s Nephew, just as the latter had feared. “This is the idea behind my new baby name algorithm, Beybi.” He handed us his card so we could see the wordplay at work in the spelling. “Beybi: Authority for Life,” it read. “Cute,” I said. “It helps parents choose optimal names for future search volume,” he said. “Because you only get one shot at authority. That’s what we tell them. The parents.” “Parents do love authority,” Lou Reed’s Nephew agreed. After our guest left, Lou Reed’s Nephew solicited my feedback. “I like the synergies,” I said. “You could promote this to all the Andreas who bring their Emmas in for texting lessons, maybe do a rev share?” “That’s dried up. There was a Yelp incident.” “And the insurance thing.” “In any case,” Lou Reed’s Nephew continued, clearly annoyed I was piling on his failure. “I like the thinking. Full lifecycle anxiety management. I suspected naming a child ‘Jane’ was shortsighted. Wish I’d had this in my back pocket. These sessions are so enlightening.” “Just so I’m clear,” I said. “He plans to sell parents a service for which they already have an innate capacity?” “We have to help nature along from time to time,” Lou Reed’s Nephew said. Lou Reed’s Nephew Takes a Day Off The next day, Lou Reed’s Nephew was gone. He was going on a retreat, he informed me, to “evaluate his revenue mix.” I went about my work, his absence reminding me of how things had been before he arrived. Ulugbek and I were building a database. Ulugbek was in Uzbekistan, and I was across from the cubicle that came to be occupied by Lou Reed’s Nephew. The database contained places and events. Places had locations but no times, while events had times but no locations. Events inherited locations from the places where they occurred. If a database contained all possible places and events, it would contain everything and would be a powerful tool for finding things to do, and people always needed things to do. That was the idea, but we were months late. We had been at 30-days-to-go-live for 245 days, which had taken a toll on me. There was tension as the first few deadlines were missed, but then it subsided, or seemed to. I got used to it. I no longer noticed it, except in how it affected my sleep. Renata noticed it. She noticed that I no longer slept all night in bed next to her. She found me on the couch in the morning and even when I was awake, she said I seemed to be somewhere else. I sent her the article from Procrustean Beds to reassure her. Everything would be fine. But we were deep into a metaphorical tunnel, Ulugbek and I. The light was receding but we couldn’t turn back. No one could. Everyone in the building of rented cubicles—except Lou Reed’s Nephew, as far as I knew—was building a database. The same database of places and events. It had not always been clear we were all building the same database—or parts of it—but it became clearer every day as we hurtled past our go-live dates and toward the vanishing point where the final database—the database of databases—was completed by someone. We had all started differently. Some had started with places. Some had started with events. Many had started with subsets of places and events. Places and events for throwing hatchets at walls, for example, or for smashing plates and office machines with sledgehammers in a sealed room with your friends. (None of the places and events in the database were particularly important. They became important when, and only when, you collected them all.) Our database, the instance of the database that Ulugbek and I were working on, expanded every day. A new database became publicly available and we integrated it, or we found a database company we liked, bought it—with the small amount of money I had collected from investors, including Renata’s brother, who worked in TV—and integrated that. This kept happening, which is why we were late. Ulugbek didn’t think that’s why we were late. He thought the project, itself, was impossible. “The project, itself, is impossible,” he told me one day, not long before Lou Reed’s Nephew arrived. He told me this via ticket. We communicated exclusively via tickets, at Ulugbek’s insistence. I had never met or talked to Ulugbek. I had never even seen a picture of him. Other than Renata, he was my longest-term partner. I sent him a ticket back telling him to integrate a new database we had acquired, but by then it was 5pm in Uzbekistan and he had left. He left every day at 5pm, just as I was getting started. This new database was a complete list of places where one could learn how to make things out of beads shaped like imaginary animals. Unicorns and yeti and pegusi. Renata used it—she hoarded beads in tight bundles stored in spaces I could not see—which is how I found out about it. It was surprisingly large, both Renata’s secret stash and the database. Renata and I agreed not to talk about the former—it was her only vice—and it was good luck that our credit card statement had unearthed this trove, which Ulugbek integrated while I read about how the Sumerians invented writing to catalog all their sex toys at The Imp of the Perverse. The next day, the cubicle across from me was empty. My opening looked across the aisle into its opening, where there was now only a pair of chairs and a few scattered thumbtacks. There had been two young women there before. Women Lou Reed’s Nephew’s age with hair dyed grey and pulled up in handkerchiefs—Rosie-the-Riveter-style—their arms marked up with tattoos. I couldn't entirely make them out, the tattoos, but they appeared to be images of tools torn from dictionaries. I wanted to tell them—didn't they know?—that there wasn't anything already more beautiful in the known universe than their plain, creamy arms? But their arms were not there to please me—I learned that in college—and it was too late now. Tattoos are tattoos. The South African came by to sweep up the thumbtacks and I asked what their business was. “Database.” he said. “Like you. They sold out for big money. Bigfoot beads. Who knew?” The cubicle stayed vacant for a few weeks, which concerned me. Had the database-market softened? Had we held out too long? Then, one day I arrived later than usual, after 5pm in Uzbekistan, and as soon as I stepped off the elevator, I heard him—Lou Reed’s Nephew—muffled only a little by the security door. |

To keep reading Lou Reed's Nephew serialized on Substack, click here:

Brief excerpts from Issue #2

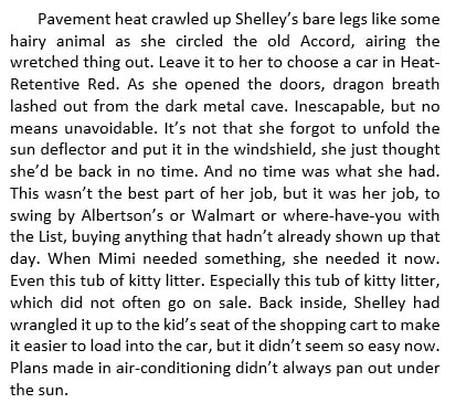

From Arroyo Circle

by JoeAnn Hart:

by JoeAnn Hart: